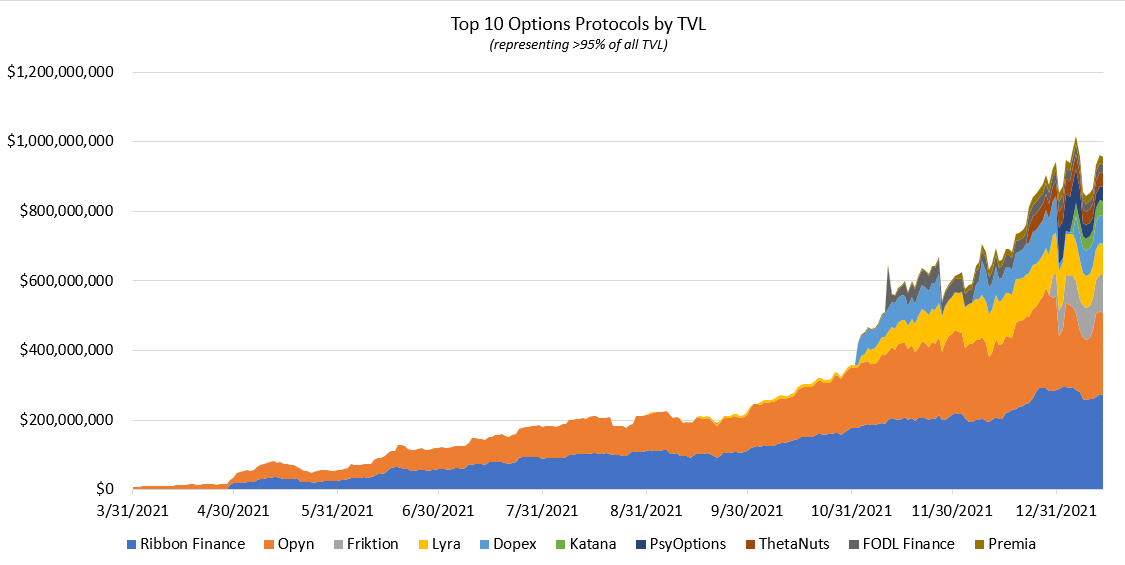

While still extremely immature compared to their equity counterparts, decentralized options products are starting to gain traction on-chain, with protocols surpassing a combined $1B in Total Value Locked (TVL) for the very first time this year.

Of these, Dopex stands out as a particular interest due to its unique token economics (surprise, it has 2 tokens!) and its plan to involve itself within the Curve Wars. This series will focus exclusively on Dopex.

In this piece, I will aim to explore what options are, the existing market structure (in the US), and the general rise of options over the years – both crypto and non-crypto. The next couple pieces will cover the ins and outs of Dopex itself, and potential valuation scenarios.

Before we dig into the broader landscape, let’s understand what options are.

Options

An option is a type of derivative: a financial contract whose value is derived from that of an underlying asset. An options contract gives a buyer the right, but not the obligation, to either buy (call) or sell (put) an asset at a set price (the strike price) within a certain timeframe. The two types of options are:

Put Option – the buyer has the right to sell the asset at the strike price

Motive: the buyer expects the price of the underlying asset to go down

Call Option – the buyer has the right to buy the asset at the strike price

Motive: buyer expects the price of the underlying asset to go up

There are two types of option styles, which dictate how expiry is considered:

American – the buyer can exercise the option at any time prior to its expiry date

European – the buyer can only exercise the option on its expiry date, not before

Since all options on Dopex are European, we’ll focus only on European options going forward.

An important advantage that options have over other derivatives is that the buyer has no obligation to exercise the contract – if it’s not profitable to exercise the option, then a rational buyer simply won’t. Hence, giving the buyer – you guessed it: ~options~. 😊

Options Marketplace

So far, we’ve only discussed options from a buyer’s point of view. However, as with any market, there is both a buyer and a seller. The options market is no different. The seller (often called ‘writer’) will create options contracts (either calls or puts), containing expiration dates and strike prices for a particular asset. The written contracts then get listed, and willing buyers purchase contracts that meet their desired constraints.

Generally, you’re an options seller if:

You believe an asset will trade with low volatility through a given period of time

On the other hand, you’re a buyer if:

You believe an asset will trade with heightened volatility (producing a strong repricing of the underlying in a single direction)

Example

Let’s go through an example to crystallize this a bit:

Amy wants to sell John a house for its current value: $200,000. John is interested because he thinks the house will increase in value, but he doesn’t want to pay the $200,000 today. Instead, John wants to buy a call option on the house with a strike price of $200,000 and expiry 6 months from now. Amy is happy to sell him a call option because she doesn’t think the price will increase in that time. Additionally, she collects a premium* ($10,000) when selling him the option. (Note: Amy has no equity in the house).

*This is the first mention of premium but it’s an extremely important term. Whenever an options contract is purchased, there will always be a cost imposed on the buyer and collected by the seller. The price (premium) of the contract is dependent on multiple factors, including time until expiry and the underlying asset’s proximity to the strike price.

Potential outcomes to the above scenario:

Outcome 1 - In-the-money: 6 months later, the house is now valued at $300,000. John exercises his call option and profits $90,000, after factoring in the premium

Outcome 2 – At-the-money: the house is valued at $209,999 upon expiry. John will not exercise his call option because the value does not exceed the strike price plus the premium paid

Outcome 3 – Out-the-money: at expiry, the house is valued at $170,000. John again will not exercise the call option for the same reason as in outcome 2

If we look closely at the potential outcomes, two things should be immediately evident:

In 2 of the 3 scenarios: The seller pockets the premium as modest profit, while the buyer forfeits it as a modest loss

In 1 of the 3 scenarios: the buyer faces unlimited upside (in exchange for an initial upfront cost), while the seller faces unlimited downside potential

From this, it’s clear that options can result in windfalls for buyers and massive losses for sellers, especially in the unhedged form we just discussed (known as trading options naked).

Hedging

At the core, naked options trading simply means taking an options position without having a position in the underlying asset. It can be quite risky. A common hedging strategy is to sell ‘covered’ calls. The seller can mitigate their losses by simultaneously holding a long position in the underlying asset.

Let’s go back to the example above with Amy, John, and the house – this time around Amy is actually the homeowner, having bought the house previously for $180,000.

From her perspective, the outcomes are:

Outcome 1 - In-the-money: house valued at $300,000 at expiry – the option is exercised. Amy receives the premium and effectively sells her house for a $20,000 profit, netting her $30,000 – of course, she’s missed out on a potential windfall of $100,000.

Outcome 2 – At-the-money: the house is valued at $209,999 upon expiry. The option is not exercised. Amy has both collected the premium and seen the value of her home rise.

Outcome 3 – Out-the-money: at expiry, the house is valued at $170,000. The option is not exercised. While the value of her home decreased (-$10,000), she effectively recouped that loss with the premium received (+$10,000)

In this altered scenario where Amy is selling a covered call, she is guaranteed to make money if the value of her home rises above the strike price. In the case where the option expires out of the money (asset price below strike price), she manages to limit her losses (even if unrealized).

Option Complexity

While I won’t go into detail here, it should be understood that complexity of options strategies exists on a spectrum. Amateur options buyers tend to trade naked without understanding that while this is a simple strategy, it’s probabilistically unprofitable. Options strategies can become quite complex, with more skilled traders combining puts and calls in multi-leg orders.

US Options Market Structure

The lifecycle of an options trade in the US looks something like the below:

The process is relatively straightforward:

An investor interacts with their broker-dealer (i.e. Robinhood) to initiate an options trade

The trade is routed by the broker-dealer to a national securities exchange (i.e. Cboe Options Exchange), where it’s executed

The details of the trade get passed along to a clearing agency, that then clears and settles (exchange of money between buyer and seller) the trade on the next business day (what’s known as T+1)

With this breakdown, it becomes clear that intermediaries touch the trade at multiple points along its journey.

The broker-dealer provides the interface through which a customer can access the market. The exchange itself oversees steady function of the market and facilitates buyer/seller interactions. Ultimately, the trade ends up in the hands of the clearinghouse – for options in the US, this is the OCC (Options Clearing Corporation). The clearing entity acts as the buyer to every seller and vice versa. They exist to ensure all parties involved honor their contractual obligations.

In a world full of imperfect humans, third parties are needed to instill trust. The parties involved in the above process ensure steady function of the market and provide access to all types of investors. Their involvement is objectively good and necessary.

However, it should be noted that the system functions with its own set of drawbacks:

Transaction latency: in a time when fiber optic cables are ubiquitous, transactions take days to settle (options in T+1, spot equities in T+2). This follows historical precedent, when securities were delivered by physical receipt and a lag existed between transaction and settlement dates

Rent Seeking: Intermediaries are inherently rent seekers. They extract value, whether directly or indirectly, throughout the process flow.

Counterparty Risk: although there are strict rules in place for maintaining the integrity of 3rd party institutions (like the OCC, for example), one cannot rule out the possibility of default, which would collapse such a system.

Trends in Options

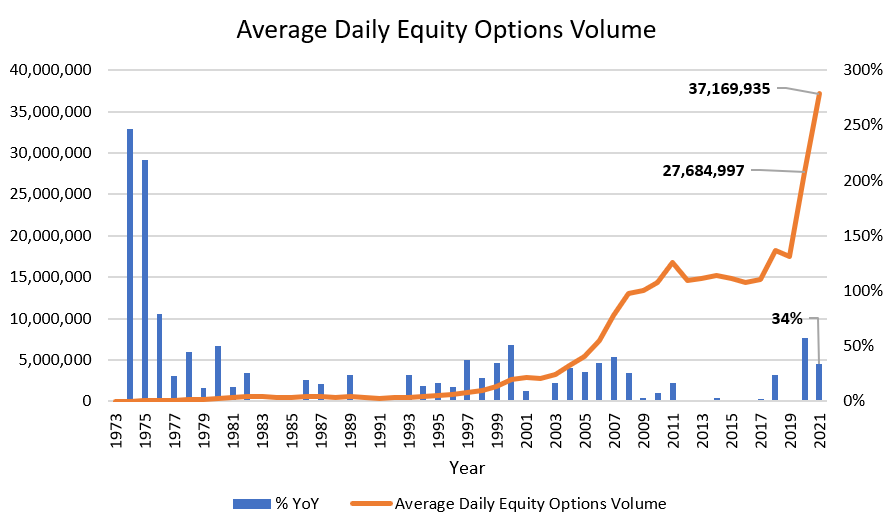

US Options trading volumes have picked up, most notably in recent years. This sudden spike has been buoyed notoriously by retail traders, who have piled into meme stocks on zero-commission apps like Robinhood.

While overzealous retail may account for the recent surge in options activity, it does not explain the broader uptake in options volume. After all, options volumes in the US have seen a pronounced trend upwards over the last several decades.

Some reasons for this sustained trend:

Hedging – institutional capital can sit long in spot while making short term directional bets on volatility/ price movements

Taxes – 60% of the gains made trading options are considered long-term capital gains, and thus get taxed at a lesser rate. This condition applies regardless of the contract’s expiry

Adding Perspective

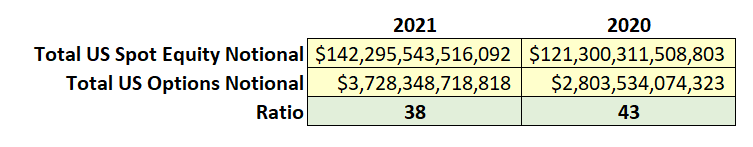

To put the volume figures in perspective, let’s consider US Equities Spot volume:

Spot trading volume runs at hundreds of multiples of options trading volume. Make note of this – we will reference it again shortly.

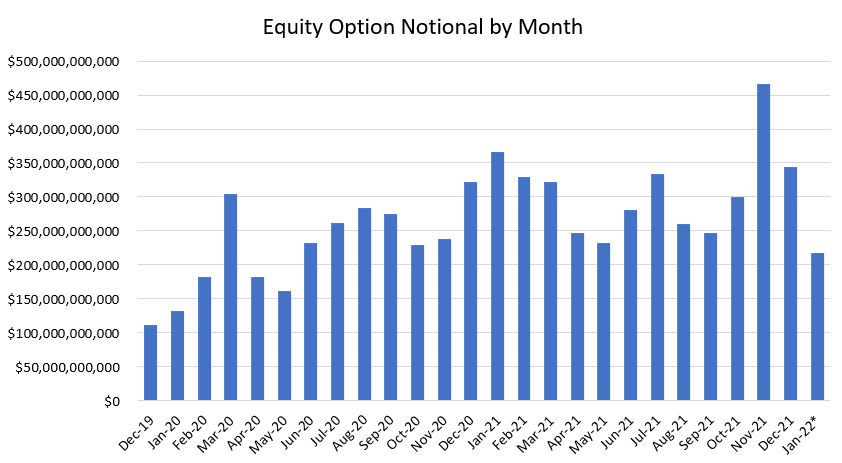

The multi-decade uptake in options volume is interesting to observe, but how does this translate to dollars? Consider a term: notional value. It is defined as the value of shares that are controlled by an option. Notably, it is not the value of the premium.

As an example, a stock is currently trading for $25. In this case, one option contract controls 10 shares. If Sweta purchases a single call option, the notional value would be $25 x 10 shares = $250. This is the value represented in the below figures.

As options volume ticks upward, so too does notional. Total US Equity Options notional in 2021 was $3.7 trillion – a 33% increase from 2020.

If we compare spot notional (simply the value of the shares traded) to options notional, we notice something peculiar:

The ratio of spot notional to options notional is noticeably lower, when compared to the ratio based on raw volumes. This is because options themselves naturally introduce leverage. Buyers of call options pay a small premium for a potentially huge payout. The dollar figure that is controlled by a single option can be orders of magnitude larger than the amount controlled by spot (as evidenced by the difference in ratios).

Now, what if we compare this to crypto?

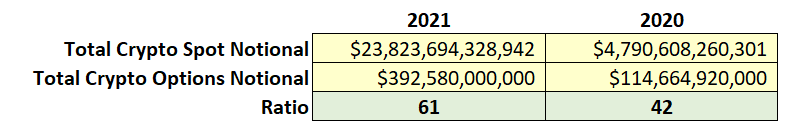

The figures themselves are a bit more difficult to glean, but the below begins to take shape:

The ratios are oddly similar to equity ratios. Perhaps not what was expected, given crypto’s relative newness.

Looking at this, it’s not clearly bullish or bearish for crypto options volumes…

Room for Growth

So where does room for growth exist exactly?

For a discerning reader, it’s clear by now that crypto assets tend to be more heavily traded than their equity counterparts.

The above suggests that a small increase in the total crypto market cap would have a larger impact on crypto options trading volume than the same increase in equities market cap on equity options volume. At 2021 ratios, a total crypto market cap of $21T would be enough to produce the same options volume as in the equities market – a crypto market cap that is roughly 40% of US Equities market cap today.

Yet, this is simply suggestive of a case that should be obvious: asset class growth begets options growth. Let’s dig deeper.

DeFi Options

To present, we haven’t really given any mention to DeFi at all, a topic which should presumably lie at the center of an essay on a decentralized options protocol. But that’s about to change..

What’s crucial to understand is that all of the above crypto options figures come from centralized entities that adhere to the same processes and pitfalls of equity options trading. They go through the same intermediaries and they yield a similar user experience.

What’s more is that current crypto options trading is confined to the two most liquid assets:

BTC and

ETH

Now, let’s reconsider the $1B in TVL sitting within options protocols. Let’s assume that TVL is notional volume that can be controlled by options contracts. And let’s further assume that options trading and expiry occurs only once every month, yielding $12B in annual notional volume.

Compare this to existing crypto volume: DeFi options represent up to ~3% of centralized options volume.

A mere 3%.

As we know, composability in DeFi offers several unique advantages:

Options products in DeFi can be built for virtually any deposit-able asset, offering a leg up compared to current centralized offerings

Other protocols can build on top of decentralized options products, offering their own unique solutions and deploying special strategies to unlock yield, growing options volume while knocking down barriers to entry for DeFi/ options participants

Lending and borrowing can be looped to offer extreme leverage if desired, etc.

Of course, the greatest advantage for individual users and investors is value accrual through tokenized ownership of these protocols, something not possible with an entity like Deribit.

Which ultimately brings us back full circle… to the point.

Why do we care?

Options volumes are on the rise and have sustained a staggering half-century of growth. Recently, crypto options themselves have grown in tandem, to the point where they mimic equity options volumes on a proportional basis. Currently, all options trading (crypto and non-crypto) is subject to the same execution and settlement processes and thus, the same shortcomings inherent with the existing system.

Using current figures, we have conservatively deduced that DeFi options volume is roughly 3% of existing crypto options volume, which itself is scaling with broader crypto adoption. Given the inherent advantages and capacity for ownership within DeFi, users stand to benefit greatly.

At worst, these DeFi options protocols simply mimic the growth in total crypto market cap and options volumes on-chain remain rather tepid. At best, they suck liquidity from centralized crypto services and become the de facto means of trading options, even stealing market share from equity options as synthetic assets proliferate.

Put simply:

DeFi options protocols appear ripe for substantial value accrual.